How Colleges Learn

The Intentional Design of Community Experience to Drive Culture Change

Jeff Goldenson, words & media

Doyung Lee ’16.5, illustrations

Olin College of Engineering, community

Summer, 2020

How Colleges Learn

In 1994 Stewart Brand published an eye-opening book, How Buildings Learn, that explores how people shape their buildings over time. I wish he’d write a follow-up called How Colleges Learn to empower college constituents — the staff, students and faculty — to shape their colleges over time.

Until that happens, you can play a game of “find/replace” to get a preview. Swap the word “college” for “building,” and with a little imagination, sound guidance awaits. Here’s a nice articulation of the problem from the book’s introduction:

Almost no buildings colleges adapt well. They’re designed not to adapt; also budgeted and financed not to, constructed not to, maintained not to, regulated and taxed not to, even remodeled not to. But all buildings colleges (except monuments) adapt anyway, however poorly, because the usages in and around them are changing constantly. (Brand, pg.2)

Over the past five years, a group of staff, faculty, students and I have been working to leverage culture and community to change Olin College of Engineering. Olin is a small, project-based learning college, and for a number of us, college culture has become the project. If asked to articulate an animating speculation behind our work, we could do a lot worse than citing Brand:

What would a building college look like and act like if it was designed for easy servicing by the users themselves? Once people are comfortable doing their own maintenance and repair, reshaping comes naturally because they have the hands-on relationship with their space, and they know how it actually works and will have ideas about how to improve it. (Brand, pg. 189)

I think a college might look and act like Olin did in early March, 2020.

Faux-mencement

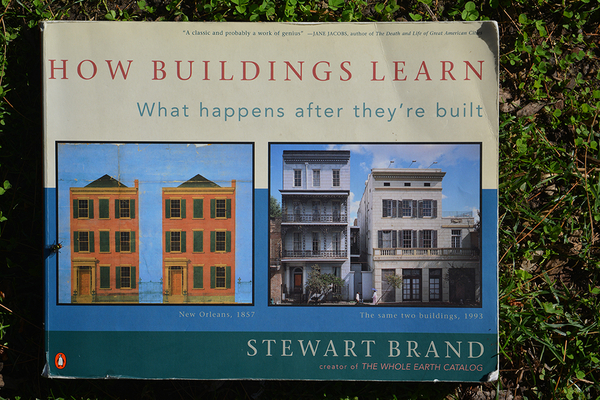

On Tuesday, March 10th at 4:06pm a long email titled “Olin COVID-19 Important Updates” arrived in the inbox of every staff, student and faculty member at Olin. It came from our founding President, Rick Miller, and was written to inform the community that “students should not plan to return to campus after spring break.”

About an hour later, a brief message came across a very different channel, carpediem@olin.edu — Olin’s student-owned mailing list for last-minute, serendipitous opportunities. This one was titled “Group Scream on the great lawn 5:40 EOM”. (EOM = End of Message)

By the time a few students and staff had gathered around a table the next morning, nothing was normal. We were in the Greenhouse, a small creative studio just inside the entrance to our academic building. In the Greenhouse, we grow young ideas, and some plants. Joining me were Susan Mihailidis, Director of Academic Affairs and Sponsored Programs; Robert Wechsler, Olin’s Artist in Residence; and a quartet of students: Matt Brucker ’20, Ana Krishnan ’20, Evan New-Schmidt ’20, and Sam Kaplan ’24. For these few students who had made it out of bed, emotions ran high. The feelings deserved airtime, and the best thing we could do as staff was to honor them by listening.

After about an hour, a heaviness set in and Susan, a senior member of the administration capable of marshalling support from across the college, was ready to act. “How about a time capsule?” she challenged. As the idea bounced around the room the energy shifted. That’s when Evan ‘20 chimed in: “How about a fake commencement?” Those five words sucked the air out of the room.

Minutes later, we strode over to the Campus Center with giddy purpose to pitch the idea to our Interim Provost and frequent collaborator, Mark Somerville. The Campus Center houses Olin’s only dining hall, which most mornings doubles as Mark’s office. And there he was, on the far side of the room, back to the wall, reliably in his black turtleneck. Ana ‘20 took the lead and pitched the idea as the rest of us looked on. Mark’s reply, “What do you need to make this happen?” gave us the green light to get moving.

Robert Wechsler captured the moment on his phone

Walking back to the Greenhouse, Matt ‘20, who not an hour before was rightly consumed by the shock of a senior spring evaporating, turned with a vigorous grin and a shrug of disbelief, “We’ve got something to do!”

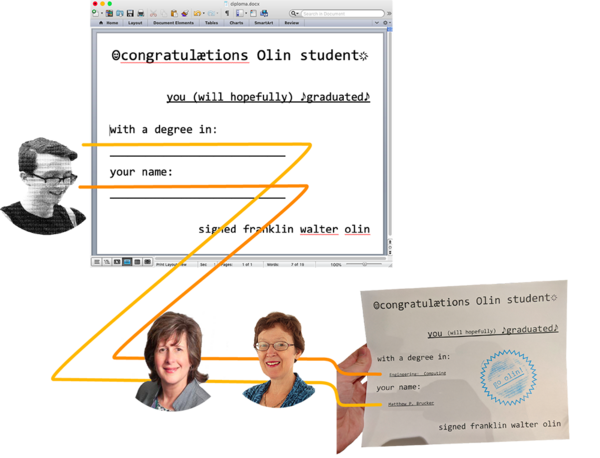

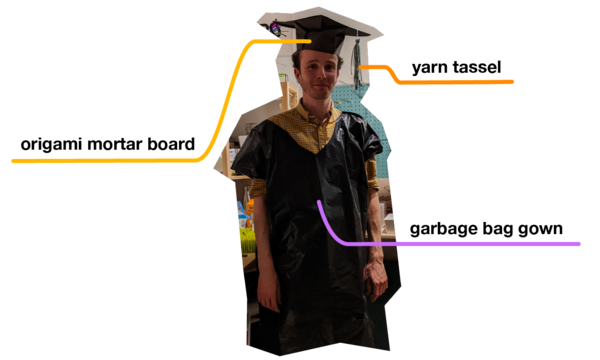

From that moment, a spirit of co-creation swept the campus. Faux-mencement was a community-owned affair. Matt and Ana sent out a pitch-perfect Commencement Announcement that looked like a ransom note. Olin hadn’t rented the caps and gowns yet, so someone found an origami mortar board “how-to” and a decision was made to don garbage bag gowns. Diplomas that read “☻ congratulætions Olin student💥…” were sent to the Registrar’s Office so names could be matched with almost-earned degrees. After checking and re-checking for accuracy, the faux-diplomas earned the imprimatur of our Registrar, Linda Canavan. Then Adam Novotny ‘21, rubber stamped ‘em with a freshly laser cut “GO Olin!” stamp.

Late that night at Stay Late and Create (SLAC), Olin’s weekly festival of creativity, students folded origami mortar boards and trimmed trash bag gowns. Meanwhile, the commencement speakers — President, Provost, honored faculty, staff and students — who thought they had three months to write remarks, worked overtime.

As for Faux-mencement itself, the sincerity was palpable. Emotions were as raw as they were joyful. The Olin Conductorless Orchestra played video game themes as Olin’s leadership marched down the aisle. Somewhere between the candid remarks of the Senior Greeters, the ceremoniously applied hand sanitizer between handshakes and the symbolic sliding of yarn tassels across paper caps, the rite of passage was vivid.

Faux-mencement matters because it was a pure expression of “Olin-ness” at the very moment we needed it most. It was a demonstration of institutional agility and college-scale collaboration that we could be proud of. On the eve of exile we came together to co-create the ritual of closure we could’ve lost. We took commencement back for ourselves, leaving Olin with a story.

If Faux-mencement demonstrates a principle, it’s Brand’s:

Age plus adaptivity is what makes a building college come to be loved. The building college learns from its occupants, and they learn from it. (pg. 23, italics original)

The Greenhouse

Since Olin’s founding in 1997, the curriculum has been “designed for easy servicing” (Brand, pg. 189) by faculty and students alike. The paths to follow and people to talk to are known. Consequently, iterating on and reshaping the curriculum has come naturally and consistently since day one. Reshaping the college, however — the antiquated hierarchies, power dynamics, and politics that keep the trains running — there’s no “easy servicing” there. Where in a college, any college, would you even go to do that work?

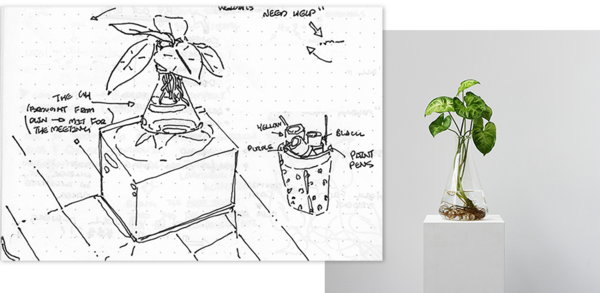

Sketch by Dieter Brehm '22 of the Greenhouse icon by Olin Artist-in-Residence, Robert Wechsler

At Olin, you’d go to the Greenhouse. The Greenhouse is a different kind of college interface -- not an office, a department, or even a traditional greenhouse — but a community of staff, students and faculty from all corners of the college committed to maintaining, repairing and reshaping Olin. We share a table, a studio space, a set of values, and the belief that college is a joyful design opportunity yet to reach its institutional potential.

Find us Wednesday mornings at 9:15 in the Academic Center Room 102, we’re the first thing you see.

Welcome to the Greenhouse

Meetings take place during Faculty Meeting — it’s a wonderfully expansive two hours on campus, you feel like you have the run of the place. We catch collaborating faculty and senior leadership in the less-hurried moments in the hour before and after. We start by brewing some coffee and playing some music while we catch up with each other. When a quorum is present, we circle up. The agenda is only loosely set. The key is we show up, making time in our schedules to build — if nothing else — relationships. Trusting relationships across constituents are the foundation of everything Greenhouse.

So what do we do? In the Greenhouse we stage demonstrations, or “demos.” We don’t demo products, we demo culture — our culture. Greenhouse demos are explicitly designed human experiences to honor and reinforce a set of values and a way of being in college together as a community of co-creators. Faux-mencement was a demo.

We stage these demos in the margins — the less contested times outside the academic calendar and curriculum. Often the demos are a kind of “pop-up” - the temporary takeover of a familiar space with unfamiliar conviviality. Pop-ups are high-leverage - for the brief time they’re happening their “leave-no-trace” ethic allows them to take center stage and be the center of attention.

Ask an engineer what a demonstration is and she’ll abbreviate it to a “demo” and tell you it’s “a practical exhibition and explanation of how something works.” Ask an activist, and she’ll describe “a public meeting or march protesting against something.” A Greenhouse demo explicitly designs human experiences that embody generous hospitality, listening, and consciously leaving official roles and titles at the door. It’s a soft demonstration.

How do we stage an organic, compelling demonstration of culture?

- Invite Everyone to the Table

- early, often and without agenda

- Find Room in the Margins

- of the curriculum and the academic calendar

- This is Show Business

- not “tell business,” we are designing entertaining experiences people choose to engage with

The Faux-mencement wardrobe, as modeled by Evan New-Schmidt '20

Though compressed into 26 hours, Faux-mencement follows these steps. It began with students and staff around a table, and drawing in the Interim Provost when we had a plan. It was staged on the lawn over lunch, in the margins of space and schedule. With homemade regalia, diplomas, and a live-stream for the parents back home — Faux-mencement was a show — it was meaningful entertainment for us all.

Olin 3rd years Grace Montagnino, Abigail Fry, Anusha Datar, taking it all in. Photo © Leise Jones Photography

Build Week

Build Week poster by Dieter Brehm

In early December 2019, just a few weeks before winter break, I was driving to Olin listening to National Public Radio. Because Olin is an underwriter, occasionally their promotional messages are read by the radio hosts. Somewhere along I-90 that morning, as I listened to the Olin message being read, I realized it had changed. The new message announced Olin 20/20, our celebration of Olin’s first twenty years as we look ahead to our next twenty, all in 2020. It took hearing the announcement over the airwaves on my commute to understand the significance of the moment for the college.

January is a quiet moment in Olin’s academic calendar. Students are at home, the college is calm — there’s room. Since Olin’s founding, the idea of doing an on-campus January intersession experiment had been in the air, but never happened. With Olin 20/20, we had our opening.

I went to the Greenhouse, made some coffee and made a pitch: let’s honor Olin 20/20 with a “back to our roots” January experiment in student, faculty and staff co-creation! Y’all want to do it?

The students were in and I stepped back. It’d be a heavy lift, it was December 10th, just seven days before students would leave for winter break. The idea was to add seven days of “open space” to the calendar beginning January 15th. Fortunately, the idea would be a win for the Advancement folks — it was an audacious and authentic way to kick-off Olin 20/20 in 2020.

A meeting was called in the Greenhouse and Olin’s leadership was excited. If students could demonstrate interest and commitment to executing all student-facing dimensions of the experience, there was a possibility. That week, while finishing up classes for the semester, the Greenhouse students took on the notion, called it “Build Week,” and made it their own. To convince administration, they drafted the Build Week Constitution: A Case for Build Week:

We’re approaching the year of Olin 2020, which calls for additional contemplation and planning for the future of Olin as a community and institution. Reflection during the semester schedule is encouraged and valuable, but the hectic nature of the semester doesn’t allow in-depth time for it. Olin Build Week is a time dedicated solely toward building community, reflection, and goals for the next 20 years of Olin. (The Build Week Constitution)

In a month that included the winter break, what began in the Greenhouse quickly became an Olin-wide idea that the students made a reality. But it wasn’t the reality I envisioned. A few days into the break, a call with Dieter Brehm ‘22, one of the lead student organizers, provided a necessary correction. All the grand framing I thrust on Build Week in service of Olin 20/20, and my own results-driven definition of success, was exactly not the point.

In mid-January, forty students returned to campus for a seven-day demonstration of institutional caretaking.

Maintenance

More is being spent on changing buildings colleges than on building new ones. (Brand, pg. 5)

Colleges are constantly performing maintenance. Large teams of folks manage the buildings, staying atop a never-ending backlog of repairs while fielding crises as they inevitably emerge. But what about culture and community maintenance — true college maintenance? Who takes care of that?

In the Greenhouse saw this opportunity and made it our creative practice. We make the rounds to check in with folks. We call it “gardening.” We try to catch concerns or issues before they bubble-over. We’re a college resource to swiftly respond to the needs of culture and community, opportunities and crises alike. We have the will and access to organize immediate action. In the case of Faux-mencement, across our team we had the relationships to text the Interim Provost; the Registrar; the Facilities Manager; first years on up through fourth years — and expect immediate response.

Convening around an idea or issue is a powerful way to work, but time and again, engaging students, faculty and staff in physical maintenance was our royal road to the cultural and community maintenance we were after. Any inquiry into the minor adaptation of the built spaces of Olin runs right up the flagpole. The inquiring team quickly finds itself in conversation with multiple stakeholders in the college, with real concerns from varying perspectives, seeking compromise. By its very nature, community-performed physical maintenance requires respect and trust across roles, duties, and ages. The act is a demonstration of the values and way of being together we’re after.

And from a resource utilization and management perspective, we’ve found its a robust path to a well used and loved space. How we changed the Library, our process, was far more important than what the changes were. Our goal was to elicit a feeling in our patrons — “I have the permission and resources to do things here.” The adaptations and repairs themselves --the products -- were not what paid the lasting utilization dividends, it’s that our process seeded a culture of community agency and ownership. Our community knew its members changed the Library, and they could too.

Doyung Lee, illustrator, during last semester at Olin in 2016 Izzy Harrison '18.5 and Annie Barrett, Barrett Architecture Studio- Stewardship

- Students appreciate the sense of ownership that comes with maintenance, and become caretakers and stewards of that space.

- Culture

- In the creative redesign process, a vitality of place emerges

The opposite of adaptation in buildings colleges is graceless turnover. The usual pattern is for a rapid succession of tenants, each scooping out all trace of the former tenants and leaving nothing that successors can use. (Brand, pg. 23)

Olin Workshop on the Library

The Olin College Library sits at the front door of the college. Walk into the Milas Hall Atrium today, and to your left is admissions. To your right, a huge student-made sign reads “Library” in reindeer moss. Passing through the glass doors, propped open with student-made hexagonal planters, you’ll find a pair of reclaimed wood tables greeting you with new & noteworthy books. The room is lit by a curved bank of double-height windows lining the western wall. It is perhaps the most beautiful space on campus.

But when I came to Olin as Library Director in 2014, the Library was a ghost town. There was no moss sign, no planters, no student creativity on display. There was neither character nor charisma, it was just another empty controlled college space.

At that time, Aaron Hoover, Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering, was the faculty lead appointed to chart a new, more energetic future for the library. Aaron was on my hiring committee and fortunately we hit it off immediately. Just a few weeks after arriving, Aaron and I set off on a campaign to invigorate the Library. We called it OWL, Olin Workshop on the Library. Our pitch to the students was simple: Every one of us is at Olin because we believe in project-based learning. Olin has given us the Library is a project, wanna help?

That first semester we began by inviting students to the Library for weekly lunchtime discussions. At the outset, we gathered data. The students created an open-ended form and interviewed peers in the Dining Hall. A strong signal came back: “A Room of Requirement” was requested in multiple independent interviews. I was in the dark, so I had to ask. According to the Harry Potter Lexicon, the Room of Requirement is “a magical room which can only be discovered by someone who is in need.” If you have a need, the room satisfies. What the students wanted was “open space” to shape for themselves.

There was a large room at the back of the lower level of the library with no natural light. This was the “Storage Room,” approximately 700 square feet of space off limits to students. With a little archival guidance from the Library team and disposal guidance from facilities, the OWL students carved out a Room of Requirement within a week or two.

The Room of Requirement 🖐🏽 Drag white dividing bar above for the Before/After

Word of the room spread quickly and then-senior Chris Lee ‘15 came by the Library. Chris ran a student organization called Stay Late and Code (SLAC). They wanted to welcome more forms of creativity so SLAC was becoming Stay Late and Create. To kick off the new identity they were hoping for a new venue.

It didn’t take long for the new SLAC to become an anchor of Olin culture — and five years in, it hijacks the whole Library every Wednesday night and shows no sign of fading. Only the Quiet Reading Room is spared. If you’re a Faculty member kicking off a new initiative — head to SLAC. If you’re a student looking to co-work with friends while enjoying a few free snacks and some music — head to SLAC.

Shortly thereafter, the ultimate “requirement” for the room emerged. Students wanted a public space to make a creative mess -- room for screen printing, art-making, materials storage and the like. We retained a contractor, replaced carpet for easy-cleaning vinyl tile; plumbed a slop sink; and the “The Workroom” was born. It turned out, the only requirement for a successful Room of Requirement was a willingness to engage students as people (not folks who fill out forms); give them the benefit of the doubt; and say yes.

There’s also a bit of an inversion of process. When you renovate a space, the expectation is you begin with the program. What will the room do? What we’ve found is there are requirements, or “programs” in architecture-speak, that need time to come out of the woodwork. Beginning with the gift of open space and open program is frequently appreciated by the community. Our best work emerged when we led with opportunity, not idea.

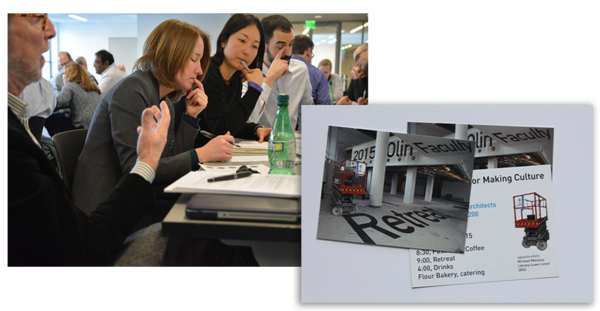

In January 2015, not long after that first SLAC event, Aaron and I hosted the faculty retreat, “Making Space for Making Culture,” on the future of the Library. This was our time to listen and learn from the faculty. As a result of the retreat, four themes came through loud and clear:

- Community — People wanted a crossroads, a place that facilitated more staff, faculty and student interaction.

- Flexibility — We needed to employ Olin’s commitment to prototyping and iteration in our pursuit of the Library. We needed maximum flexibility to try things.

- Action — There was an energy in the room that day, a chance to try something new at the College. We needed to act fast to keep that energy alive.

- Coffee — The word coffee came up with enormous frequency.

At the time, the first floor of the Library was spacious but inflexible. Strung together in long rows in the center of the space, the bookshelves consumed the main floor. Inspired by the retreat, we wanted to let the community “borrow” the room to host an event, and then reset the space, returning it to a functional library. How might the main floor be its own room of requirement for the faculty and larger college community? We started by putting everything on wheels.

In one afternoon, fueled by the best bagels and cream cheese money could buy , the students mounted swivel casters to the bottom of the bookshelves. It was a safe and scrappy retrofit. If you wanted to put a date on when a new culture of the Olin Library was born, that Friday, February 19th 2015, would be it. The community came together turning The Library into a mixed-use venue.

The Heart of the Library 🖐🏽 Drag white dividing bar above for the Before/After

In the process, we hit on a formula that guided much of our work in the Library:

- Pitch students on making a dramatic change to a public space

- Make it a party , encourage folks to play music, slow down and have fun

- Spend hundreds feeding them memorable food

- Save thousands by retrofitting existing resources with our own hands

- Buy a nice camera (that students can borrow) and document everything

- Check with Facilities beforehand to ensure safety and feasibility

That summer, emboldened by what we saw students could do in one day, we created OWL Summer Design/Build. For eight weeks we set seven students free to create the library the community wanted. We worked hard, played music, ran a book club, swam in Wellesley’s lake, brewed coffee and called it learning.

No academic credits were harmed, or rewarded, in the creation of this picture.

The Team Rooms 🖐🏽 Drag white dividing bar above for the Before/After

This is Project Based Learning

When we claim maintaining and adapting the college as project-based learning we foreground the unique “do-learn” opportunities embedded in the practice. Olin’s engineering coursework revolves around teams making things. Organizational change, college change, focuses on teams making things happen. This work requires collaboration across all constituents, engaging the broadest spectrum of folks.

Introducing anything new amidst today’s health & safety concerns, insurance policies, fire codes, shrinking budgets and competing agendas is hard work. It also makes for rich learning.

The Greenhouse Summer Report Out, Summer 2019 with Emily Nassiff '21, shot by Doyung Lee

If a team of students wants to work with staff and leadership to make something happen in college, they need to understand how college works. They’re motivated to look behind the curtain. And there they see the college for what it is: a universe unto itself complete with its own issues and idiosyncrasies, people and politics. This is “do-learn” organizational change. To make any headway takes careful thinking and planning.

- How do we frame x?

- How do we do x with the resources at hand?

- Who should we talk to first?

- How do we satisfy students and administrators simultaneously?

- How might we measure success?

It’s hard to teach this kind tactical thinking, this kind of hustle, inside the curriculum. Walk out of the classroom and into the halls of power and tactical thinking is critical. Making change at Olin is good practice for making change in the world.

Beginning

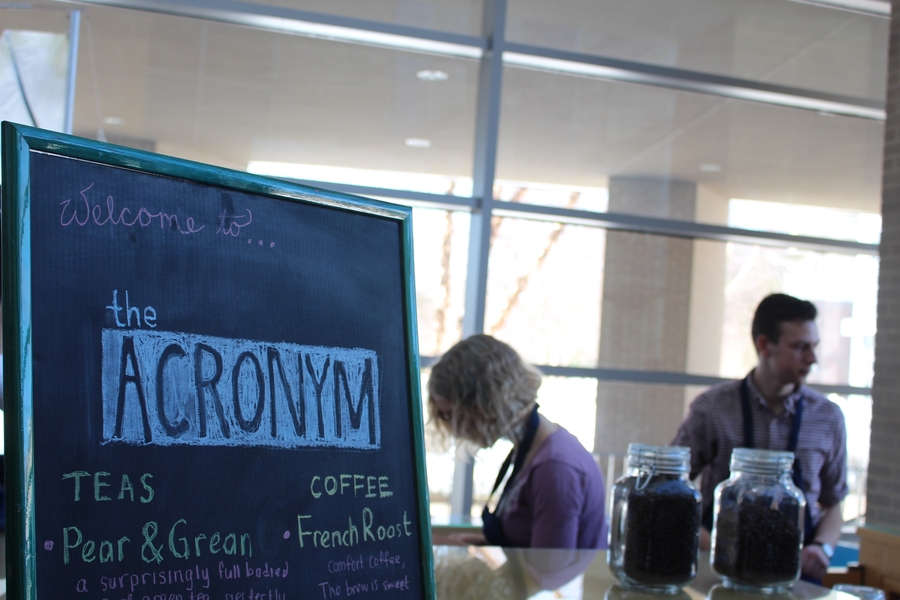

So where do you start? Start with a small, easily repeatable demo and provide something people want. You can’t go wrong with coffee. Perhaps you start where we did, with a regularly scheduled pop-up community cafe — free coffee, free conversation. The students named it the ACRONYM.

- Free Coffee & Tea

- Wednesdays, 12:30p-2:30p

- Milas Hall Atrium

- Fresh-brewed pour overs

- Served by student volunteers

The coffee’s delicious and it takes forever - turns out pour-over coffee delivered by novice baristas is a slow, inefficient proposition. And while at first the long lines seemed a bug, they quickly proved a feature. What folks don’t pay in money, they pay in time -- time spent in line chatting, listening, spacing out -- building community.

the ACRONYM (which is not an acronym), checks all the boxes:

- Invite Everyone to the Table

- Everyone gets an email invite, everyone gets a beverage.

- Find Room in the Margins

- The ACRONYM pops-up in the Milas Hall Atrium, the front door of the college right outside the Admissions Office and the Library, temporarily energizing the empty security desk to everyone’s pleasure.

- This is Show Business

- ACRONYM sets the stage with all the details: there’s a chalkboard with specials, a playlist, and matching aprons. And not to leave Olin without free coffee during exam week, Faculty baristas now step up and host “FACRONYM.”

Five years in and fully owned and operated by students, ACRONYM has become a fixture. It’s a weekly, three hour demonstration of the students’ vision of Olin in the heart of the college. And for those three hours once a week, our college is a different place.

This is Social, Work

A college is not a building. A building is a material construction -- lumber, hardware and ductwork. A college is a social construction -- policies, protocols and beliefs established between, and carried out by, people. A college learns as its culture learns.

A fake graduation, a week of repair, a summer co-creating a library, a free cup of coffee -- this is the joyful, social, work of changing college by demonstrating culture.